How do you communicate consciousness, one of science’s most persistent enigmas? For more than a century, neuroscientists, physicists, and philosophers have tried to locate the point in time and space where subjective experience emerges from objective matter, yet the bridge between brain and mind continues to evade formal description. Competing frameworks of how scientists can organise neurological knowledge in order for it all to make sense have failed to resolve how perception becomes self-perception. Even evolutionary accounts that traced consciousness to cognitive advantages have struggled to explain how these computational processes acquired what remains best described as an inner light.

Perhaps the bigger problem is that science was built to measure objects, but now it must somehow account for a subject. Until it can describe experience without reducing it to mechanism, consciousness will remain an unfinished frontier.

Art, however, is born of that inner light, and its expression has long sought to give shape to the unmeasurable continuity of awareness itself. The long sentence, in particular, has always tempted writers who believe consciousness refuses to stop at the period mark. Across languages and centuries, novelists have stretched sentences until they mirror the mind’s own digressive, recursive, and porous impulses.

Its better exponents (in the author’s limited view) in more recent times include Thomas Pynchon, William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, W.G. Sebald, and László Krasznahorkai — winner of the 2025 Nobel Prize in literature — for pushing this pursuit to its limits. Their sentences are the stories themselves, architected using breath and memory.

Playing with the structure

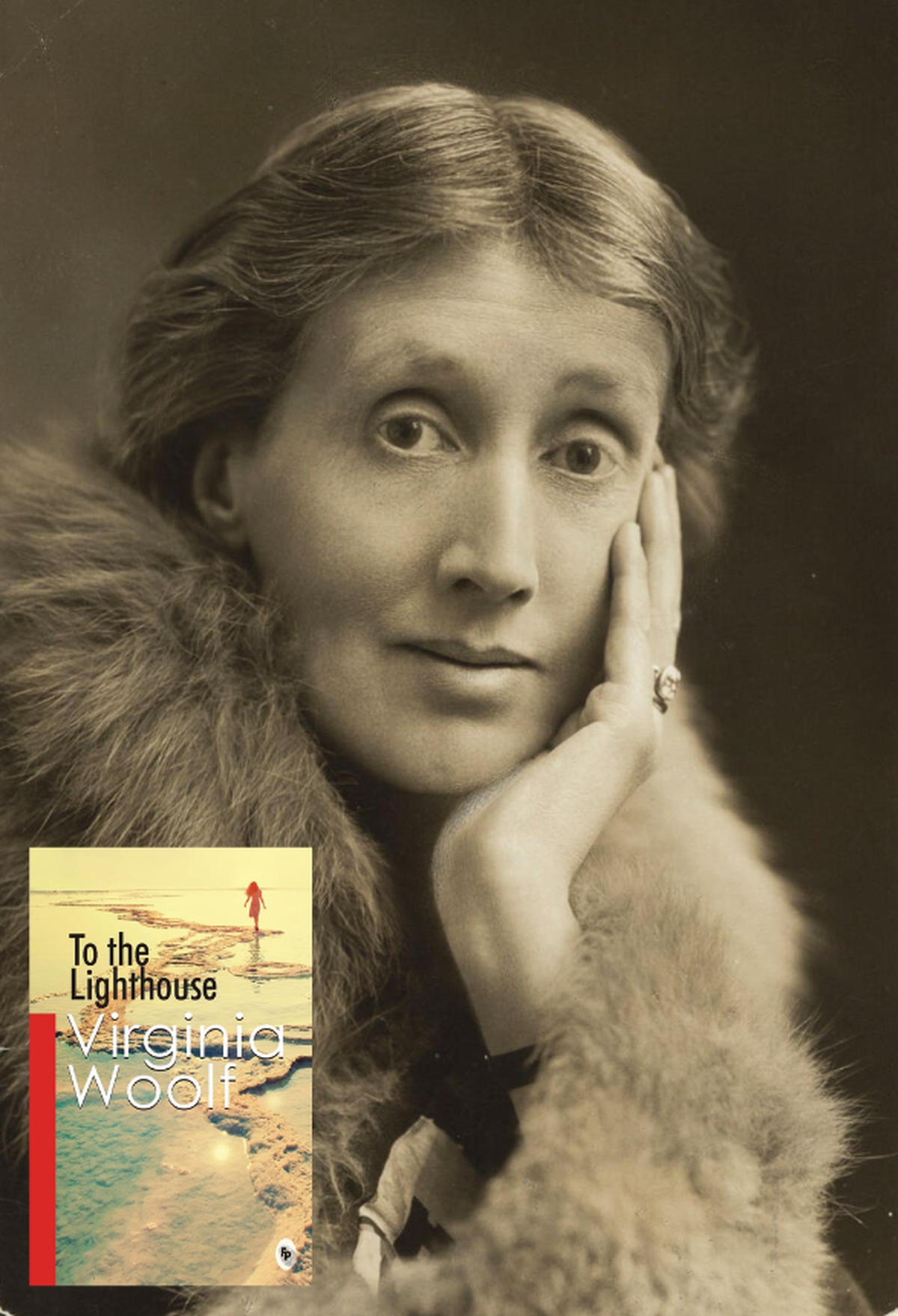

For Woolf, the long sentence was a way to turn consciousness into narrative form. For both the Ramsay family’s promised trip to a lighthouse in To the Lighthouse (1927) and the six choral soliloquies of The Waves (1931), she replaced the usual order of cause and effect with a rhythm that moved like thought, fluid and filled with sudden illuminations. Rather than describe characters moving through the world, Woolf traced how they felt the world passing through them, and thus the shimmer of light on water could expand into memories of childhood, loss, and desire. Punctuation was a breath in the mind’s own tide, capturing the ceaseless effort to hold the present before it vanishes. The English writer achieved what science still struggles to: a language that describes consciousness from within.

Virginia Woolf

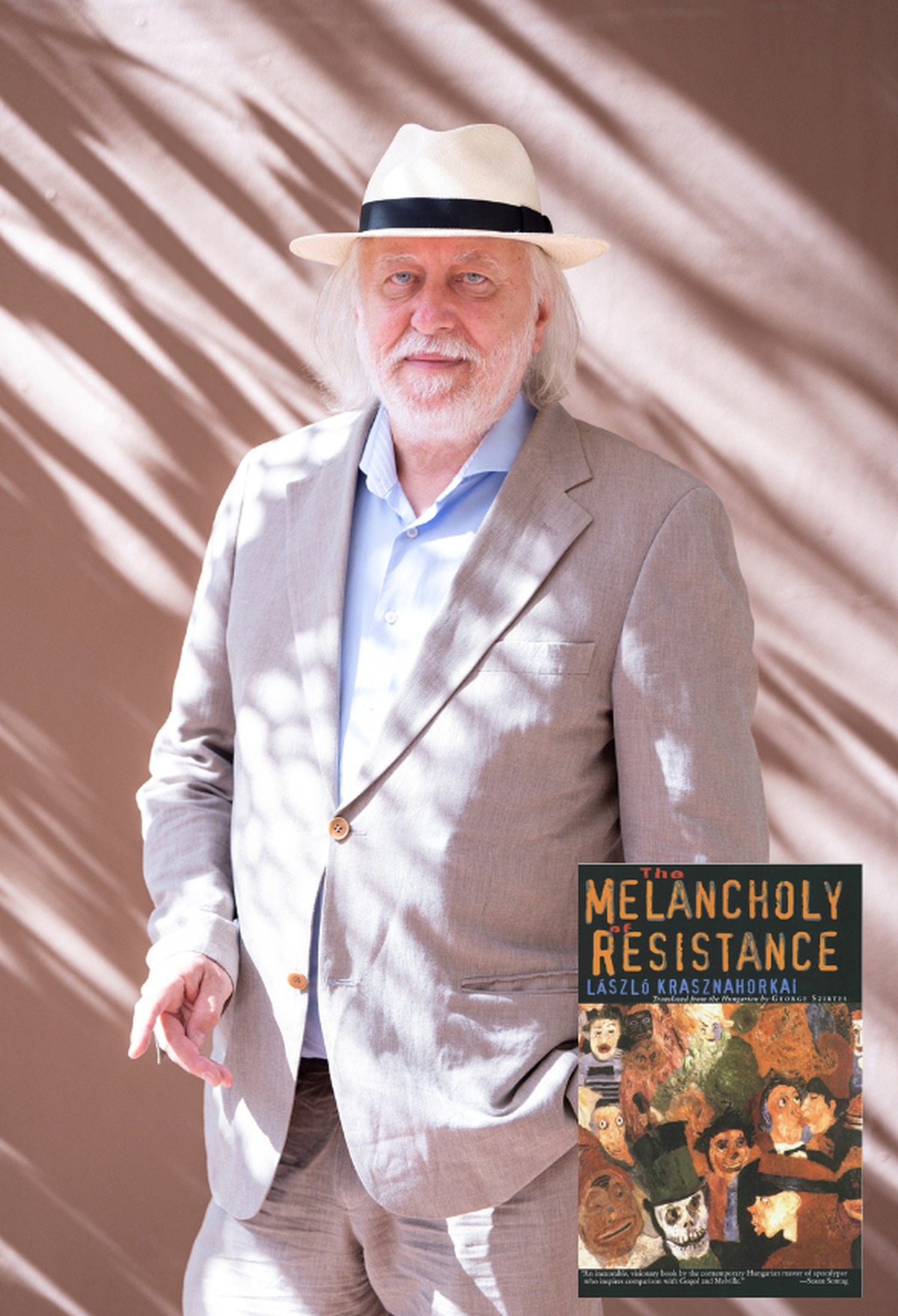

For Krasznahorkai, on the other hand, the long sentence was a means to the end itself. In The Melancholy of Resistance (1989), a small town unravelled when a mysterious circus arrived, carrying a giant dead whale and rumours of chaos. The prose echoed the spreading panic: paragraphs running for pages, joined by endless conjunctions that refuse to let the reader rest. The result is both claustrophobic and hypnotic as narrators perceive decaying towns, futile revolts, and a cosmic weariness without respite. The Hungarian novelist’s sentences are an unstoppable, biblical flood, yet within that torrent is a strange serenity, the possibility that they could hold the ruins together a little longer.

László Krasznahorkai won the Nobel Prize for literature on October 9

With Pynchon, however, they fall apart, or perhaps they were always that way. In V. (1963) and Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), he built rapid, centrifugal narratives filled with rockets, corporations, conspiracies, and jokes — all spinning out of control. Mirroring this entropy, his sentences’ clauses pile up, crammed with technical jargon and historical detours. Reading him is like surfing the data stream of the 20th century, where everything connects to everything else and nothing stays coherent for long. The sprawl is a kind of realism for an age of excess.

Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow

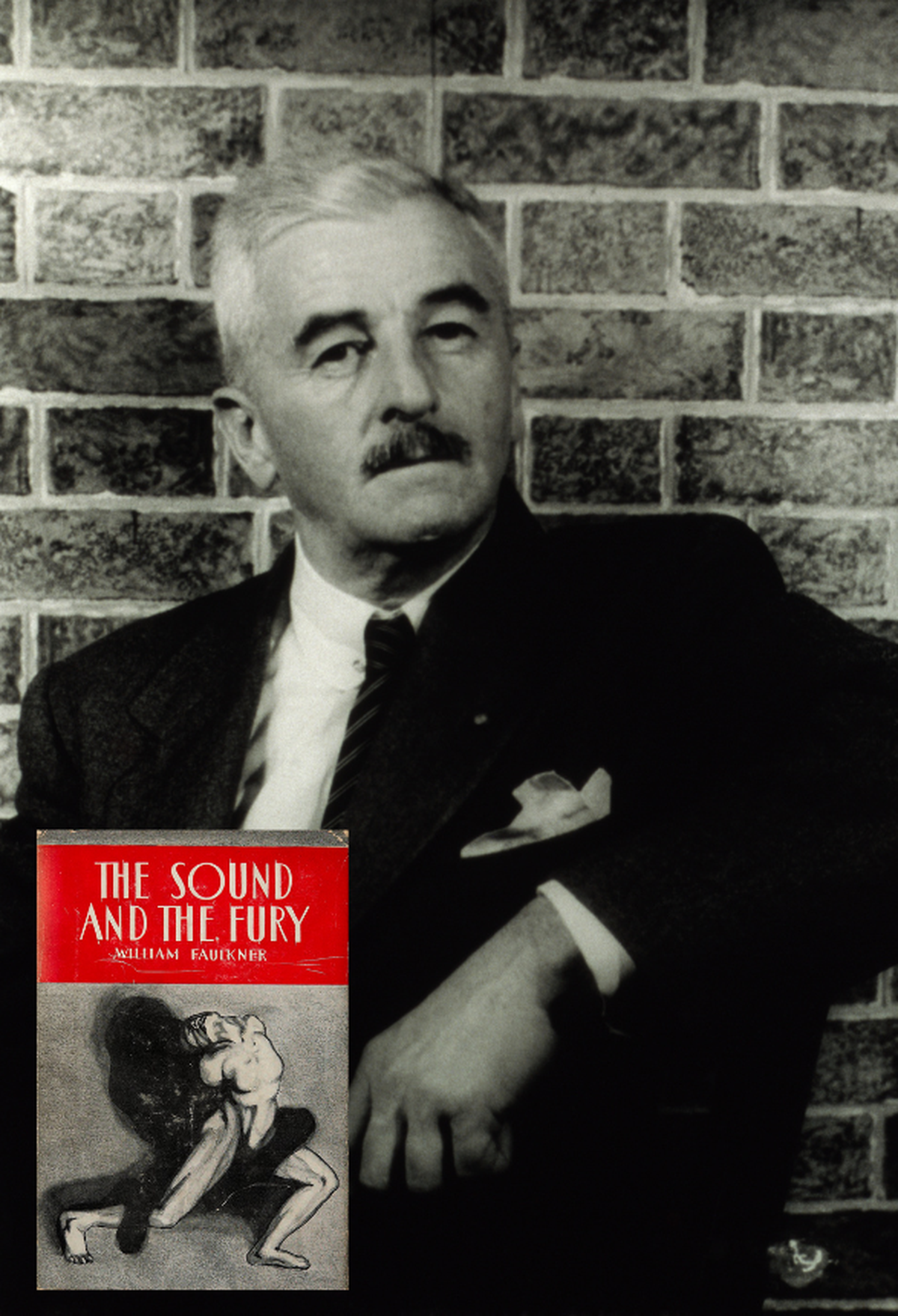

William Faulkner, writing from the haunted South of the early 20th century U.S.A., used the long sentence as a vessel for memory and guilt. In The Sound and the Fury (1929) and Absalom, Absalom! (1936), entire histories had to unfold within a single paragraph. His sentences often looped, self-intersected, and refused to finish for fear of facing their consequences, mimicking a mind circling its own pain. A memory of a family dinner could suddenly become a betrayal or a death. By allowing sentences to wander in this way, Faulkner wielded grammar like psychology, with every pause or omission feeling like repression made audible.

William Faulkner

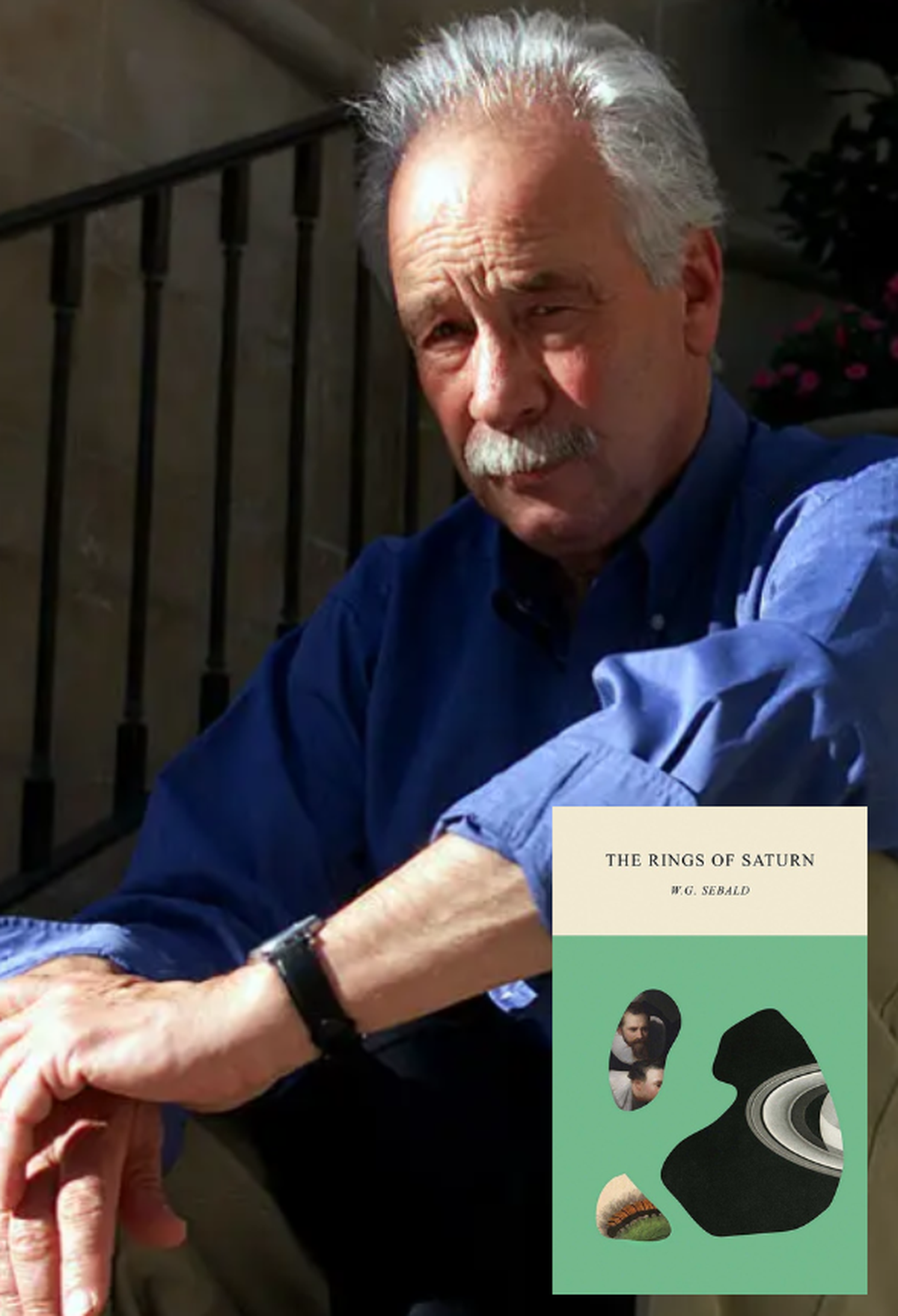

For Sebald, finally, the long sentence was an elegy. In The Rings of Saturn, the German author walked the coast of East Anglia while meditating on the slow erosion of landscapes, empires, and lives. His paragraphs drift without hurry, moving from a photograph to a ruin to a historical anecdote as if time were a continuous mist. Unlike Pynchon’s manic disorder but closer to Krasznahorkai’s constantly impending cataclysm, Sebald’s restraint forced the reader to make peace with the slow erosion of meaning over time, until the sentences became heavy with the weight of remembering.

W.G. Sebald

Shaping the reader’s senses

Comparing these writers reveals the long sentence to be a spectrum. Even more recently, among many others, Irish novelist Mike McCormack used it in Solar Bones to bridge death and life; American-British writer Lucy Ellmann in Ducks, Newburyport to deliver a tour de force on the state of America; and French novelist Mathias Énard in Zone to collapse geography and memory. Their choice reflects a shared intuition that the architecture of the sentence can shape the reader’s sense of time, space, and morals — probably an absurd notion in this age of compressed communication. The long sentence, after all, forces cognition to slow to the tempo of thought and renders language itself an experience.

Their choice has also revealed that awareness is not discrete or divisible, as neurons and algorithms would have it, but continuous — a rhythm that outlasts the body, gathers the past within the present, and spills into imagined futures. In the authors’ long and winding lines, language became an experiment through which consciousness learnt to witness its own unfolding.

Published – October 11, 2025 04:12 pm IST

#Consciousness #art #long #sentence